Goodbye, Mother Tongue

/by Chantal Braganza & Kelli Korducki

Immigration from one country to another can mean learning a new language. Along with that, however, comes a separate, if related, linguistic struggle: maintaining the family’s original language(s) and the associated cultural ties.

The Americano Dream?

Ten years ago, the late political scientist and policy advisor Samuel P. Huntington published his last book, Who Are We?—a highly controversial treatise on the origins and apparent erosion of the American identity. One of the threats? Mexican Americans who still spoke Spanish.

He argued that more than earlier European immigration waves to the U.S., Latin American newcomers were more likely to retain their mother tongue since, dialects aside, the Spanish they spoke was largely the same. For Huntington and likeminded thinkers, who believed English and America were inextricable, this was a problem.

“There is no Americano dream,” he wrote. “There is only the American dream created by an Anglo-Protestant society. Mexican Americans will share in that dream and in that society only if they dream in English.”

But the problem with Huntington’s assertion itself, aside from being presumptive and more than a little racist? He had his facts wrong. A couple of years after his book’s publication, sociologists from the Woodrow Wilson School and the University of California-Irvine scaled data from two recent immigration adaptation surveys. They found that even in areas of the U.S. with high Mexican and Latin American origin populations such as southern California, “language death”— not being able to even order at a restaurant in Spanish, even if your mother tongue is fluent— was pretty much a done deal by the third generation.

“The death of immigrant languages is not only an empirical fact, but can also be considered part of a widespread and global process of ‘language death’” wrote the study’s authors. “Whether or not this is desirable, of course, is another question altogether.”

Spanish-speaking immigrants to the U.S. aren’t the only cultural group grappling with involuntary language loss. As the reporter James Kim wrote in an award-winning 2012 feature for Southern California Public Radio, studies have shown that the trend applies across the board While the first generation of immigrants speaks their native language and the second generation tends to be bilingual, the third generation loses the native language altogether. Kim cut to the chase; a second-generation immigrant (that is, the American-born son of Korean immigrants), he lost his mother tongue around age seven. A Cal State Long Beach professor assured him was not atypical. He wrote: “It was a relief to find out that my ineptness towards speaking Korean was actually common in my immigrant generation.”

Similarly, Portuguese-Canadian blogger Fernanda Viveiros laments her own inadvertent language loss:

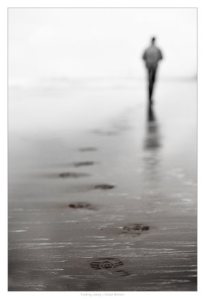

I wonder if most immigrants carry this burden of existential angst about the loss of their language and how this loss created a communication barrier between them and their children. However much our parents may have encouraged us to speak English in order to assimilate, I think they were saddened by the repercussions of introducing a new language into the family home. Losing one’s mother tongue is often the first step—the largest step—towards moving away from one’s ethnicity towards a new identity and culture.

As University of Toronto professor Jim Cummins plainly puts it: “Children's mother tongues are fragile.” Without dedicated effort to maintain that mother tongue, within a dominant culture that speaks something else, fluency in that first language will quickly collapse.”

“He who knows but one language knows none”

There are a couple of different translations of this popular Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe quote, but they all get at the same point: knowing more than one language is good, and even better if it started from an early age. So what are some of the upsides that two-tongue speakers have on the rest of us?

- Stronger brains. (No seriously; bilingualism often means denser grey matter.)

- Better multitasking skills.

- An easier time learning a new (third? fourth?) language.

- A better chance of fighting off age-related cognitive decline. There’s a bunch of studies to suggest that bilingual people have a better time maintaining cognitive reserve (i.e. well-oiled brain function) into their senior years.

- More complex creative thinking. Apparently knowing how to navigate more than one language, more than one type of grammar, and more than one set of words to describe your environment helps you to connect things that aren’t immediately obvious.

And to all the monolinguals out there? Plenty of these benefits aren’t exclusive to people who’ve been speaking more than one language since an early age. There’s still plenty of time to take a class or pick up a Rosetta Stone kit. Or, if you’re anything like so many second or third-gens with language loss guilt, pick up the phone, call your mother, and say hello in her home language.