Black Lives Matter in Brampton, Too

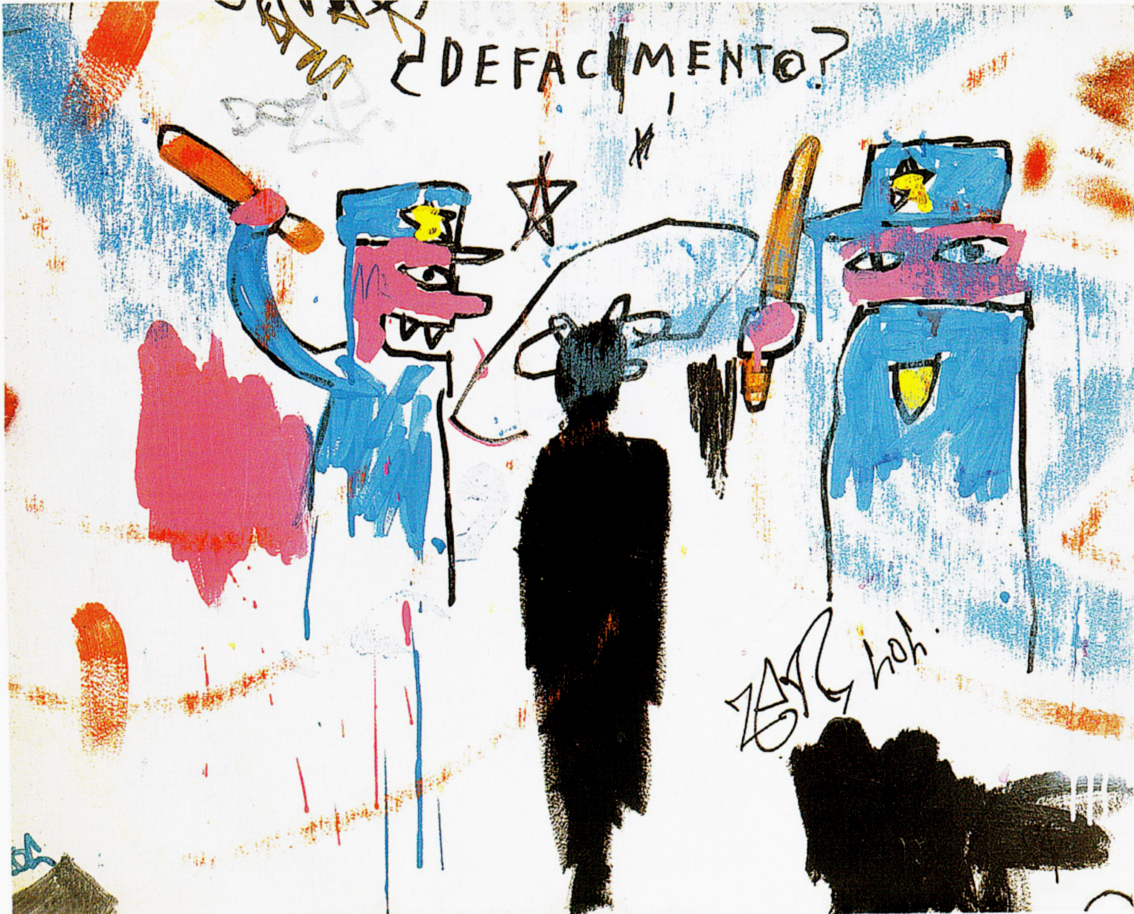

/Basquiat: The death of Michael Stewart

By Anupa Mistry

I found out that Jermaine Carby was killed by a police officer from the movers. On an mild-ish day last October, I was sitting between the two of them — the Bajan one with dimples, and a Jamaican guy with glasses — in the cab of the truck they’d diligently loaded with all of my stuff. As the Bajan guy drove we engaged in a mild flirtation, while his partner poked at my cat through the mesh of her carrier. They told me they lived in the west end, and couldn’t imagine dealing with all the people and traffic downtown. They marveled and cursed at cyclists weaving in and out of lanes. We must’ve passed by, like, five cop cars on the 15-minute drive over to my new place, and a different conversation began. “Cops are everywhere these days, eh?” said the driver. “You can’t move without feeling like something’s going to happen to you. A guy just got shot by a cop in Brampton, eh?”

My heart stopped and my hands went clammy for about 10 seconds, before I began to ply them with questions. Who was Jermaine Carby? (A guy from Brampton) How old was he? (33) Who shot him? (A cop, during a traffic stop) How could I have missed this news? (They shrugged)

I haven’t lived in my hometown for almost 10 years now, but my parents are still there and it is a place — beleaguered by white flight, and still thriving — that I've become fond of and glad for over the years. Before I even knew what was out there I wanted to leave Brampton, but once I actually left I learned its pervasive reputation as the region’s trashcan made me defensive.

People call the city “Bramladesh.” Much of the derision, from both outsiders and residents, has to do with it being a hub for immigrants. Well, sure, it’s close to the airport and abundant in relatively affordable housing suitable for working class families like mine. In the mid-90s, we moved from a small apartment overlooking Chinguacousy Park into a newly built subdivision called Springdale, which young people – and then their parents – re-christened as “Singhdale,” on account of all the Punjabi families. We said these things as jokes, because everywhere we looked there were brown faces.

Twice now, I've driven by the spot where Carby was shot, an intersection on the cusp of the city’s old downtown. There was an Olive Garden there once, and a dilapidated Party City that’s been replaced by a Shoppers Drug Mart. A quick three-minute walk north on Kennedy is Central Peel High School, which everyone, but mostly the Jamaican kids I grew up with, called “Central Africa,” because, well, you get it. Nowhere else, except maybe parts of the UK, will you find kids who greet their friends with both a Punjabi ‘kidhaan’ and a West Indian ‘whagwan.’ In no other jurisdiction, could you find a judge so dismayed at a lack of available Jamaican patois interpreters.

Brampton is a city of over half a million people, Canada’s ninth largest. It has booming development and a nimble transit strategy that’s kept pace. It is a hotbed of basketball talent, and a key battlezone between federal Liberals and Conservatives. And guys, there’s even an Aritzia in the mall now.

Different corners of the GTA have their flare-ups of civic pride (and yes Scarborough, we know, Drake loves you). Yet Brampton is routinely overlooked, treated as a punchline, brushed aside as the bumbling little brother to the wealthier and/or whiter boroughs that encircle it. The thing about the way the GTA was built is that despite municipal borders we are all connected; whether you live downtown or in deep Ajax, there is nary a greenbelt that separates us.

“In no other jurisdiction, could you find a judge so dismayed at a lack of available Jamaican patois interpreters.”

Our financial, culture and ideological core is in Toronto, though Brampton is its own distinct city. Stories haven’t just been lost: in trying to create a mythical, homogeneous metropolis out of a populous and disparate region, there’s been a quiet, permanent absorption of narratives that don’t fit. When we don’t hear stories in, or originating from, the 89 different languages that Bramptonians speak, we’re missing out on valuable information about how the city, a city that feeds the Megacity.

When we ignore these stories we lose perspective. And as such, when incidents such as the police shooting death of Carby happen they go unnoticed. Even by people like me, hailing from those parts but now reliant wholly on whispers from friends or, in this case, the movers.

In late November, the non-indictment verdict in the case of Ferguson, MI’s Mike Brown — and the concurrent anticipation for a verdict in the case of the police choking death of NYC's Eric Garner — brought at least a few hundred people out to a peaceful rally in front of the US Consulate on University Avenue. Members of Jermaine Carby’s family were there to speak about his case, which is still under investigation by Peel Regional Police, and to further link Torontonian rage and sadness about the American news to events closer to home. On Christmas Eve, 50 people, led by Justice for Jermaine Carby, held a vigil at the site of his death in Brampton.

Lives lost to structural and moral inequities are lives lost: Mike Brown and Eric Garner and Tamir Rice and Anthony Robinson and Freddie Gray are just as important as Jermaine Carby. All of these black lives matter. But it’s difficult not to feel unsettled by the disproportionate silence on Carby. Torontonians are capable of action — take the summer 2013 protests against the College Street shooting death of Sammy Yatim by Toronto policemen — but there are parts of the GTA, further flung, that are neglected by outsiders as well as residents.