My Big Fat Non-Traditional Wedding

/Bhairavi Thanki discusses why she isn't going to have any of her family's Indian traditions in her own wedding, no how, no way.

Read MoreBhairavi Thanki discusses why she isn't going to have any of her family's Indian traditions in her own wedding, no how, no way.

Read MoreSpeaking with Denise Balkissoon, sexual health counsellor Rahim Thawer discusses HIV prevention, fetishes, stereotypes and, most importantly, keeping the ass fun.

“Being both Muslim and queer always seemed like mutually exclusive identities to me.” Rahim Thawer explores how he came to see queerness and Islam as compatible, at least in himself.

Read MoreMy mom's not a jeans and t-shirt type of girl.

And now in her mid-50s, it's doubtful she'll ever be one. My mom feels most comfortable in the traditional Pakistani shalwar-kameez, a loose-fitting tunic top and flowing pajama-like pants that billow in the wind every time I see her walk out of our Mississauga home.

Her outfits often have unimaginable bright hues, anywhere from magenta to parrot green, colours that seem to blind you on a cold, tombstone-grey Canadian winter day. They always grab my attention.

Read MoreScaachi Koul worries that her arm hair makes her unfeminine. “Leg hair removal felt unavoidable, and socially required, but I figured arm hair was okay to take to the mall. I was wrong. ‘Why do you have that?’ a male classmate asked, pointing to my arms. ‘You’re hairier than I am.'”

Read MoreNavneet Alang has learned to love his totally awesome chest hair: “In the time I was busy developing complexes about how I was an impossibly unattractive yeti, Bollywood had hopped on the “ripped, hairless chests” bandwagon.”

Read MoreWhen people talk about the Great Downtown/Suburb Divide, they are also talking about ethnicity.

Read MoreVisiting India as a 13-year-old was a nightmare realized. Bad things happened: being groped by skeezed-out men in crowded places, disembarking a congested train by jumping as it pulled away from the platform, traveler’s diarrhea, seeing a giant cockroach in a hotel bathroom (my first roach!), getting a bag of chips snatched from my hand by a hissing monkey, screaming at an overly persistent street vendor from a hot, cramped car, blowing smog-blackened snot from my nose in New Delhi. I can go on (but I won’t). My reaction to all of these things was very visceral: Ugh.

Read More

Jazz pianist Vijay Iyer is a Yale mathematics graduate who also holds a Ph.D. from U.C. Berkeley in Technology and the Arts. This might seem slightly incongruous until you read the title of his 1998 dissertation, according to Wikipedia: Macrostructures of Sound: Embodied Cognition in West African and African-American Musics. There's a real cerebral element to Iyer, who speaks carefully and at length but not without laughter, that anchors much of the free-form associated with jazz's improvisational nature. Iyer also attributes much of this to a 25-year-long obsession with dramatic, oblique melodies of Thelonious Monk. Last year, Historicity by the Vijay Iyer Trio was nominated for a Grammy; it included a cover of M.I.A.'s "Galang." Iyer has also worked with a slew of rappers as a composer and writer, including a recent collaboration with post-postcolonial weirdo rappers Das Racist. A first generation curio of sorts, the unique position Iyer's found himself in has meant courting a mix of ambivalence, naive curiosity, and ferocious pride, from a varied audience from labels to critics, long-time jazz fans to inquisitive South Asians. Of course this means Ethnic Aisle had to real talk with him about what the hell it's like to be a brown jazz musician ahead of his Toronto Jazz Fest performance Tuesday, June 28, at the Glenn Gould Studio. -- Anupa Mistry

In everything written about you, the phrase “Indian-Americans” always shows up, but I’ve also read you saying that the racial paradigm is frustrating, so does that phrase ever get annoying?

Well, it’s in my bio because either people look at my name and get it or, more commonly, they look at my name and have no fucking idea what it is, you know? So that’s to kind of diffuse that tension in the first or second sentence. But also, I’m not ashamed of it: it’s made me who I am. It sets up the dynamic of difference at the beginning, but really, that dynamic is there before I even show up, say anything, or play anything so I may as well claim it.

How important is that visibility, do you think, in terms of being in a line of “non-traditional” work?

Our community only started existing in this country in the ’60s, really. That’s when the immigration law changed and the first big wave of immigrants came to the U.S. and had children. When I was growing up there weren’t any of us in culture whatsoever. This was before there were people like, even, Rushdie, you know? Now we’re on TV, and in politics (for better or worse), and in the corporate world too—and also we’re having our own scandals now! We’re in the news in a lot of different ways, some of it is tremendous, some of it is horrible—but its good when that representation gets tweaked a little. Traveling around the U.S. and meeting other Indian-Americans who come to my shows, I can see that it’s been an inspiration—especially for people who are 10 to 20 years younger than me. To be out there and doing this has, and I don’t want to self-aggrandize or anything, made some kind of difference: it’s been said to me many times and it’s meaningful and one of the reasons I keep doing it.

Okay, so my parents were weird about me listening to rap music even though they bought me Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise tape when I was, like, 8. How did you grow up with music?

I remember the first record my older sister bought was Saturday Night Fever. I was probably four or five. We had plenty of pop stuff in the house. I remember buying Prince’s Purple Rain right when it came out and Thriller too. In terms of jazz, part of it was that I learned to play piano by improvising—it wasn’t structured or guided in any way. The piano was there, and my ear had been trained because of violin so I was able to pick things out. I would try and play the songs I heard on the radio—Michael Jackson and the Beatles. My high school had a good music program and I was in the orchestra but they let me join the jazz ensemble. When I first auditioned, I didn’t know how jazz was structured so I kind of made my version of it without knowing what was going on. My band director said it was important to learn about the music—the history, the theory, the repertoire and so on. So I did that every day in eleventh and twelfth grade.

Do you remember connecting with a particular record?

I remember seeing Billy Taylor, who passed away earlier this year, on the CBS Morning Show that my dad used to watch. This was the mid-’80s so Wynton Marsalis was becoming prominent; he was on Saturday Night Live! I would check stuff out at the library— Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis—and look at who is playing on the record and wrote the songs. That path led me to Thelonious Monk. I’d heard so much about him. I think it was Monk In Tokyo and Giants Of Jazz that made me think, ‘Wow, he’s barely playing.’ There’s all this wide open space in the music and when he did play it was just one or two notes, and they’d have this elemental force. It was really mysterious to me. It was much more structural and would have this kind of cataclysmic effect, compared to other musicians who were orbiting around the music like mosquitoes. I was like ‘Is he even playing music right now?’ And that’s a good feeling, I love that feeling. I became obsessed with him and I still am really, and that’s like 25 years later.

"It was grounding for me to have elements in my own work that were linked to my heritage...It was a way for me to be myself in the music which I'd never really seen before."

When did you first start exploring Indian forms?

It’s more about rhythms for me. I do deal a little with ragas, but it’s sort of hard on a piano. I was never trained in Indian music—well, but I wasn’t trained in piano either, so who cares?! I moved to California when I was 20 for graduate school and it was sort of an identity-driven mission. Early memories of seeing Carnatic music made me curious about what the percussionists were doing, and especially in South Indian music, they’re improvising and responding to what’s happening. So I got more into the structural side of that. I was starting to become more of a composer so that knowledge was helpful in creating more variety and rigor.

But also, it was grounding for me to have elements in my own work that were linked to my heritage. In the Bay Area I connected with Asian Improv Arts. They are community organizers as well as creative musicians, so they dealt with identity in this empowering way. It wasn’t just ornamental, they had this radical sensibility that connected music to activism, so working with elements of your identity or heritage in the music was part of the whole mission and ideology. That was really inspiring; it was a way for me to be myself in the music which I’d never really seen before, at that time.

Does race still play a role in jazz?

For me, to be playing jazz is to be dealing with race. It’s such a fraught, racially-charged subculture and it is polarized. You’ll find whole communities of white musicians, who only play with other white musicians. You’ll also see other African-American musicians who only play with other African-Americans, but often for the purpose of hiring or collaborating for empowerment reasons. Elder African-Americans will hire younger African-Americans because they want to nurture them. When white people do it, that’s basically what it is but it doesn’t get named as such—that’s sort of a privilege of whiteness, not having to name yourself as white.

That reminds me, I wanted to ask you about that New York Times top 10 composer list you tweeted, kinda angrily, about…

Did you know they have SIX classical critics? It’s disproportionate! Anthony Tommasini made a list of the top 10 composers and, of course, they were all dead white males. Like, why are these guys so great? Well, basically because you and everyone in your scene says so! I mean, they’re completely influential, but can you honestly say that Mozart was the greatest musician that ever lived? Particularly though, Tommasini’s not dealing with any artists from the 20th century before 1950, and also there were no women on it. It’s just dumb. He would also happily admit that it’s a biased list and he is who he is but this was on the front page of the Times’ website for months—it wasn’t some inconsequential list on a blog. At least acknowledge how influential you are! (Laughs) It’s a cultural institution and it affects the way people think and yet this happens all the time.

The media is beyond diversity training, I think.

Well also, in a way, the language of diversity has kind of regressed in the last decade or so. I feel like, somehow, since the culture wars of the late ’80s and early ’90s, there’s been this deep backlash. People don’t even know these basic things about race and power and they act like ‘Oh, that’s all PC nonsense’ without even knowing what they’re talking about. You have such a spread of levels of awareness.

"Either you’re white and neutral or else you perform your ethnicity, like Lil Wayne or something. You can’t be in between."

Does this kind of tie back into why you think visibility is important?

Remember though, visibility doesn’t always shift the power balance. Like, black people are visible but they’re disproportionately unemployed and incarcerated and have the highest infant mortality rate. There’s still this deep power imbalance that persists well because, I don’t know, white people don’t like to share? (Laughs) My parents worked hard and created a stable environment for me, I never wanted for anything, I had a really good undergraduate education and they paid for it. So, in a lot of ways, I’m a child of privilege. But entering culture was a different thing: trying to get a record deal it was always, ‘Are people going to buy a record with your name and face on it?’ Certainly in the ’90s and during most of the last decade the answer was ‘No.’ This is still true because now they can really track statistics on different factors and variables. And it’s purely about money. So it’s on a consumer level first, then on a label decision-maker level. Either you’re white and neutral or else you perform your ethnicity, like Lil Wayne or something. You can’t be in between.

This is why I like following you on Twitter! You’re totally present and engaged instead of just being, like, quiet about all these weird machinations. Is jazz still political then?

It is for me. There are a lot of jazz musicians today who are completely apolitical, which I find beguiling. It partly has to do with who is making the music now and why. One thing that’s happened in the last couple of decades is the proliferation of jazz schools. So people will get undergraduate degrees in jazz studies or performance, usually in some sort of conservatory model, and that’s for people who can afford to do that and would over something that’s a bit more lucrative. So it’s for people who are more privileged, basically. We’re almost two generations into that dynamic.

It’s much rarer to find people who grew up in the ghetto now playing jazz, because that path was, for the most part, not available to them. Whereas 20 years ago you would find those people, and certainly 50 years ago that was all you found. That was where the music came from: that kind of real edgy (as in ‘being on the edge’) marginality and not having anything. Trying to do the impossible is what jazz is to me. You can hear the defiance in the music, and that’s partly why it has had this universal impact: not just because people were virtuosos, but there was this storytelling quality and it literally came from struggle. Maybe people hear that in some hip-hop, certainly in the early days of hip-hop. But nowadays that stuff is on display in a grotesque way because that’s what makes money, and that theatricalism is what teenaged white kids want to buy. But anyway, in terms of jazz, most people who do it today went to school for it and because they’re good at it—privileged prodigies. Those my age or younger came through that scenario, and therefore have no reason to be political because it was never their problem.

Being the first Indian-American jazz musician, I had to create possibility from impossibility. I don’t want to say it was the type of struggle that people like Monk had just to survive, but it inspired me because of that. Like, Monk was born to a single mother who moved her three kids to New York in the ’20 so her kids could legally go to high school. It’s heartbreaking. What’s my excuse for not making it? Why can’t I? I don’t find that many younger people in this music are inspired by that aspect of it, they’re often inspired by the sound and virtuosity, the beauty of music, which is itself a great thing, but it’s not the only thing.

Is that path-forging what draws you to people like M.I.A. and Das Racist?

Yeah, absolutely. It’s the same force.

Das Racist is good, but are also kind of crazy.

In terms of ‘working’ with them, this was about 75 minutes of my life! (Laughs). It was a blast, but it was also kind of a blip. They’re hilarious and we had a good time. One of the reasons we connected is that Heems (Himanshu Suri) said he liked the way I’d make jokes on Twitter. He said something like, ‘If you didn’t have mad jokes, man, I don’t know if I’d be working with you. I respect you but if you can make me laugh that makes me feel okay.’ That makes me feel glad.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJuzWCCYS7c&w=425&h=349]

What about the M.I.A. cover from Historicity?

The M.I.A. cover wasn’t something I thought people would hear and then think that I was hip. (Laughs) I admired her because of the inventiveness and the force she brought into music that was just so powerful and inspiring and seductive and kind of hilarious. It’s outspoken and not just because she talks about Sri Lankan politics, but because her identity is so undeniable. Musically, there’s nothing there that seems accessible to an acoustic jazz trio—piano, bass and drums have no place in that music! (Laughs) It’s proudly synthetic and from the digital junkyard of the third millennium, like it was put together by consumer electronics and it’s cheap but it has improbable power. I wanted to see if I could force an alignment between my group and just that one track, ‘Galang.’ It would be so unstable that it could only last the length of the song, so I was looking at the inner workings of the track, transcribing it and orchestrating it for our instruments for something we could use. It happened in a day, which is basically how our records are made anyway—they’re a snapshot of what a band is doing.

Who are you listening to now?

Craig Taborn just put out a solo piano record that’s not like any other. To me, he’s the number one pianist living today. He’s from my generation as well, but is really interesting and eclectic and aware of all types of music. I’ve been going back to folk music too, like Gnawa music from Morroco. It’s a world I can just listen to it and be in for a while. I saw Flying Lotus play live the other day here in New York. He’s really onto something. There were two or three opening acts that were cool, but when he came on it was just… I mean what I wrote on Twitter was “uncanny rhythmic truths” (laughs) because he’s found a way to make irregular sound regular. There’s lopsidedness to a lot of the beats, but the effect it has is so undeniable. It’s kind of coming out of Dilla, sort of? It’s visceral: played at that volume at a club you feel pockets of air flying around your body and you’re moving in a way that’s tethered to rhythm. That’s what I mean by rhythmic truth, truth about human motion. Musically speaking, I don’t think it’s something that’s been articulated to that degree before. I also really like Georgia Anne Muldrow, Muhsinah and Shabazz Palaces.

You retweeted my idea about the harmonium being really conducive to the melody of Fabolous’ “You Be Killin’ Em.” Any chance of making that happen?

(Laughs) Well, I actually have a harmonium but I don’t play it much. The question would really be, why?

By Navneet Alang

For all its cachet and global recognition now, I grew up hating Bollywood films. That’s not a terribly original thing for a ‘South Asian child of immigrants’ to say, but there you go. When I was young, I think I disliked them because I was relatively sure Hindi films were mostly comprised of middle aged women crying — every other scene containing a melodramatic reading of “Lekin, kyon beta? Kyon?” (But, why child? Why?) Aaand cue the histrionic weeping.

But when I got older and started to form opinions on culture and art, it was the lack of realism that bothered me most. While to this day I am no film connoisseur, it is still realism that appeals to me. My favourite films of the past few years (save Transformers 2) have all been largely understated, quiet, and most definitely unlike the typical spectacle of Bollywood.

And for whatever experiments in postmodernity and historiographic metafiction that have swept through literature, western film still seems generally committed to a vision of ‘realistic truth’ – or, in the case of fantasy or sci-if, at least internal coherence. To witness a mainstream Hindi film, then, with its generally blatant disregard for verisimilitude can be jarring for the western viewer. When one sees not only a song erupt mid film, but the characters move inexplicably to the Swiss alps, the B.C. Rockies or the streets of New York, it upsets one’s suspension of disbelief. The penchant for melodrama, the ‘absurd’ deployment of deus ex machina, the black and white construction of who is good and who is evil – all of it commits that great sin against realism: it abandons the everyday for the exaggerated and unbelievable in the service of spectacle.

But all of what I typed above also commits its own sin: it attempts to judge the aesthetic output of one socio-historical context by the standards of another. This is, generally speaking, a mistake. But though art and entertainment can occasionally be universal, they are mostly not, more often instead being products of the time, place and thought of the culture(s) from which they sprung.

Part of this has to do with the function a given work plays in a social context. Here’s Nirpal Dhaliwal in The Guardian (quoting a Sony India exec) explaining why Bollywood can seen so sprawling and scattered to non-Indian audiences:

“[Bollywood] has to appeal to a very wide demographic here. It’s not a finely segmented market like in Britain or America. Each film has to appeal to grandparents, parents, and children of various ages. Cinema is often the only entertainment choice Indians have, so it has to appeal to every member of the family as well as to different income, literacy levels, and various regional and language groups. It needs to please those who pay £5 in the multiplexes, but also those paying 10p in the lower stalls, who want overemphasis in the story and the acting, who want to whoop and clap.”

This need for inclusivity means that a typical Bollywood film is a romance, comedy, family saga and action movie rolled into one. That, Shridhar acknowledges, gives westerners the impression that they are “loosely written, meandering and don’t make sense”. But Indians are instinctively forgiving. “People will watch a film and know that the next 15 minutes isn’t going to be for them. It might be a dance sequence, or a ‘hand of God’ scene that’s for the grandma sat next to them. Bollywood films are more like a live circus or a variety show than a western three-act concept of a movie.”

That’s a little ungenerous, given how sophisticated the plotting and acting in mainstream Hindi film has become. But it does point out that the big Bollywood film is not ‘Indian Film’ as much as it is a genre or style, like the summer blockbuster or issue film. It is meant to perform a function in society, often becoming the common, shared space through which the Indian public processes issues, change and ideas. It also has to cut across demographics, the divisions of which in literacy and lifestyle are essentially inconceivable to a western audience. Understand that millions of Indian cinema attendees also can’t rely on regular electricity or read the signs at the door when they enter. (Edit: and that hundreds of thousands arrive at the cinema in new, air-conditioned cars carrying iPhones and Blackberries.)

But there’s something else running under all this too. What does the commitment to realism get us? Why do we want art to be ‘truthful’?

That is of course far too large a question for me to answer. But it’s one that has permeated western discussions of art since Plato famously banished the poets. And one current that has consistently appeared is that art should ‘hold a mirror up to reality’, and in being shown the reflection, we recognize and learn something about ourselves and the world we live in.

But what underpins that idea is as straightforward as it is complex: there is an important relation between what is shown, what we see and what is true. We do, after all, ‘see the truth of the matter’ – not hear or smell it. The visual counts. What is true can be shown, and therefore, to show the true is important. It’s also based on the idea that, even within postmodern pluralism, we believe an honest film can show us some small something of what it is to be human.

In order to understand why this isn’t a culturally universal idea, I’m going to be a bit crazy and quote the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy’s take on the concept of two truths in various facets of early Buddhist, Indian thought. Honestly, you can skip the quote, but it seems right to at least put it here:

To sum up, though this entry provides just an overview of the theory of the two truths in Indian Buddhism discussed overview, it nevertheless offers us enough reasons to believe that there is no single theory of the two truths in Indian Buddhism. As we have seen there are many such competing theories, some of which are highly complex and sophisticated. The essay clearly shows, however, that except for the Prāsaṅgika’s theory of the two truths, which unconditionally rejects all forms of foundationalism both conventionally and ultimately, all other theories of the two truths, while rejecting some forms of foundationalism, embrace another form of foundationalism. The Sārvastivādin (or Vaibhāṣika) theory rejects the substance-metaphysics of the Brahmanical schools, yet it claims the irreducible spatial units (e.g., atoms of the material category) and irreducible temporal units (e.g., point-instant consciousnesses) of the five basic categories as ultimate truths, which ground conventional truth, which is comprised of only reducible spatial wholes or temporal continua. Based on the same metaphysical assumption and although with modified definitions, the Sautrāntika argues that the unique particulars (svalakṣaṇa) which, they say, are ultimately causally efficient, are ultimately real; whereas the universals (sāmāṅyalakṣaṇa) which are only conceptually constructed, are only conventionally real. Rejecting the Ābhidharmika realism, the Yogācāra proposes a form of idealism in which which it is argued that only mental impressions are conventionally real and nondual perfect nature is the ultimately real. The Svātantrika Madhyamaka, however, rejects both the Ābhidharmika realism and the Yogācāra idealism as philosophically incoherent. It argues that things are only intrinsically real, conventionally, for this ensures their causal efficiency, things do not need to be ultimately intrinsically real. Therefore it proposes the theory which states that conventionally all phenomena are intrinsically real (svabhāvataḥ) whereas ultimately all phenomena are intrinsically unreal (niḥsvabhāvataḥ). Finally, the Prāsaṅgika Madhyamaka rejects all the theories of the two truths including the one advanced by its Madhyamaka counterpart, namely, Svātantrika, on the ground that all the theories are metaphysically too stringent, and they do not provide the ontological malleability necessary for the ontological identity of conventional truth (dependent arising) and ultimate truth (emptiness). It therefore proposes the theory of the two truths in which the notion of intrinsic reality is categorically denied. It argues that only when conventional truth and ultimate truth are both conventionally and ultimately non-intrinsic, can they be causally effective.

Now this is all very complex, and only a tiny snippet, and I can’t at all claim to understand it in any thorough way. What you can get a sense of reading through it, though, is that the idea there is a one-to-one relationship between what we can be shown in reality and what is ‘ultimately or ‘unconventionally’ real is not the same in ‘Indian’ thought as it is in ‘Western’. The very fact that the theory is called ‘two truths’ is itself already a sign that we are working in a very different set of rules, one in which immanent, experienced reality is not the same thing as ultimate reality. If you’ve ever wondered why, as Pankaj Misra said in Devotional Poetics and the Indian Sublime, that Hindus can believe the immanent world is nothing, yet still be great capitalists, there you have at least the beginnings of an answer.

This, I admit, is a very circuitous way of saying the following: cultures are complicated, and the ways in which they construct their art are related to the ways in which they have constructed their thought. What constitutes the good in art or even entertainment is something that is part of the swirling, unstable mess that is a cultural context. And it’s not like culture is ‘a thing’, fixed and unchanging. It is an ongoing set of practices, beliefs, languages and ideas that all together form a dynamic force that is itself both a product and producer of history. And if how you judge art is about what you like and what you think is right, then judging is is mostly a culturally specific act. Bollywood, like any cultural product, is working within that specificity — and, when possible, should be treated as such.

*

My favourite Indian film is one many NRIs (Non Resident Indians) have been chattering a lot about lately. It’s called Udaan (Netflix link), and is a story about a teen boy who gets kicked out of school and has to deal with his demanding, stern father, whom he eventually resists. It is an understated, quiet film – much closer in tone to the early work of David Gordon Green or, perhaps more accurately, Satyajit Ray, while still owing much to modern Bollywood technique. It’s very much my kind of film: simple, mostly about people talking, and focused on a small set of characters.

But if you are looking to understand what the ‘anti-realist’ nature of Bollywood film does best, I have two suggestions: the massively successful 3 Idiots, and the lesser known but great Khosla ka Ghosla. Both, when judged by western standards, are fragmented, ‘over-the-top’ and ‘unrealistic’. But, in a way that’s slightly hard to explain, that over-the-top-ness is necessary, as each film tries to articulate something about how India is changing. It’s almost as if the complexity of both the sub-continent’s history, and its emergence into a nation state composed of radically disparate elements in only 50 years, makes the over-the-top-ness a narritival and experiential necessity.

Now, especially in India and its film, is not the time for subtlety. The changes occurring are too vast, profound and seismic in nature for small shifts of light or facial expression to matter very much. You could, in fact, probably argue that the Western aesthete’s emphasis on subtlety as a goal is itself a product of relative social, cultural and artistic stability and uniformity. It is a luxury that history is yet to give India.

So as the IIFA awards descend on the city, and with it a slew of commentary about Bollywood, good and bad, if you can, embrace the melodrama and give up the fetish for realism — all the while, keeping in mind that as the waves of modernity crash into the walls of history, it helps when they’re really really big.

By Anupa Mistry

I’ve mostly been pleasantly surprised over the past week to see mainstream coverage of the International Indian Film Academy Awards (IIFA), taking place in Toronto this weekend. Rumour has it we beat out New York for the chance to host the star studded, nomadic, diaspora-chasing ceremony and we’ve all heard the stories about Bollywood being a global film powerhouse. Plus, mad white folks love Aish! So it only makes sense that people pay attention, right? Expecting something basic, but secretly thrilling, I landed on FLARE‘s slideshow guide to the top Bollywood stars only to get kinda grossed out with every click.

A lot of mainstream narratives that follow Indian representation in pop culture are full of shit: everything’s Bollywood, and spices, and traditionalism, and anthropomorphic deities. In the hands of inexperienced commentators, sorry, but I expect nothing less. For FLARE, in the hands of a should-be-versed commentator, Anokhi EIC Hina P. Ansari (who wrote an interesting IIFA-themed piece about her director grandfather), I found juvenile, reductive drivel?

Y’all, why was none of this stuff questioned???

Re: Saif Ali Khan, “His comic timing makes you melt and he could charm his away into the heart of any parent.”

I mean, if we’re going there, my dad wasn’t even alive during Partition and he holds an active grudge so I don’t think any Khans will be doing any charming in my household. In all seriousness, why is this parochial traditionalism even being pandered to grown-ass women capable of making their own decisions?

On Deepika Padukone: “Co-starring Shahrukh Khan, this global blockbuster propelled this Brahmin beauty to the stratosphere.”

In university my friends and I met an international student who mentioned something about caste outright. Like, 17-years-old at the time, we took this to the logical, obnoxious extreme, cackling “HI, I’M RAVI AND I’M BRAHMIN,” every time we saw the poor guy. I was hella dumb in university but even then I knew to call people out on this type of bullshit. I’m thinking of insisting on being adjectized only as a Shudra sweetheart from now on.

Filmi mag or FLARE? “Chopra is a bombshell with a capital B.”

Oh, maybe an intern did write this?

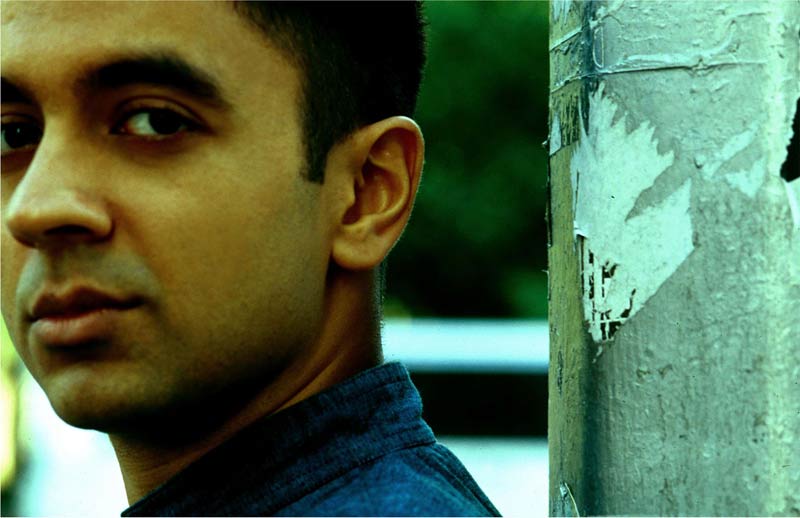

AND, they used this picture of Aamir Khan:

By Denise Balkissoon

10. It used to make me mental when my parents pronounced my name the Trini way, DEN-eeez. I would prissily inform them it was duh-NEECE. Now I wish they would pronounce it their way. I miss it. Also I wish I could properly pronounce it the French way.

9. My brothers’ middle names are Imran and Hakim. Mine is Camille.

8. My parents don’t speak French.

7. When I was in high school, my Chinese boss made my Chinese co-worker pick an English name to use at work. This, in a very Chinese neighbourhood. Someone needs to make a clever t-shirt slogan about keeping your internalized racism off of me, thanks.

6. I’m very interested to know which of the GTA’s current immigrant waves are and aren’t assimilating their names. I tried to write a story about this, but the province would only give me last name trends, or first name trends. First-and-last was an invasion of privacy. Fair enough, but I wish I could get at least anecdotal evidence among, say, Tamils, a group of relative newcomers who have seriously non-Anglo names. Thai people have crazy funky names, too, but there aren’t as many around here. Anyway, if you have ideas how I might write this, let me know. Also, if you have an unwieldy ethnic name, keep it. Or don’t.

5. Last year I worked at the Star and there were four – count ‘em, four – brown female reporters. And our names were mixed up on a semi-regular basis. Generally by men.

4. My dad’s mom apparently gave me a Hindi name when I was born, but no one remembers it. This makes me a little sad.

3. I love how names can tell you so much about where and when a person is from. I was recently talking with a pregnant friend of mine about trendy old-fashioned names, and we joked about some that would never come back, and what she might name her son. “Heathcliff Wong!” she laughed. “That’s a real estate agent in Vancouver.”

2. I’m not too fussed about mispronouncing people’s names once or twice, or having them mispronounce mine.

1. That said, why do white people always say “Balkinson”? Hooked on Phonics worked for me!

By Anupa Mistry

We all know white people listen to bands with white people in them, so why can’t I be partial to bands with brown people in them? Oh, you ain’t know there exists a significant body of work beyond M.I.A.? THERE DOES:

1. Das Racist: Here’s a sample lyric from “Ek Shaneesh” which basically made me feel 75 per cent less alone in the world:

Listening to Three Stacks, reading Gaya Spivak Listening to KMD and feeling weird about Naipaul Fly or style warz, war style Warsaw Listening to jams with they pops about dem batty boys Listening to Can while I’m reading Arundhati Roy Yeah, yeah, my pops drove a cab homes Now I drop guap just to bop in the cab home

I MEAN, WE ALL FELT WEIRD ABOUT NAIPAUL, RIGHT???

2. Shilpa Ray and her Happy Hookers: Shilpa Ray, the coolest possible incarnation of a harmonium-playing Bad Indian Girl (I can’t believe that website still exists).

3. Yeasayer: Anand Wilder: a name I’d hate on a white guy (judgy face, Devendra Banhart), but turns my eyes into hearts on a brown. [youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okxAi06PTAU]

4. Woodhands: They’re Canadian so I want to take Paul Banwatt to my former Brampton high school and make him play songs in the cafeteria underneath a sign that reads, “Choices: You Have Them.” (Only I’M allowed to make these jokes about Brampton.)

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpfvqaNCTEU]

5. Bat For Lashes: Her name is Natasha Khan and she painted her face, minus the lazy “tribal” connotations, before Drew Barrymore and Kelly Osborne. And, OMG, Gwyneth Paltrow in that “I AM AFRICAN” campaign, which makes me feel both embarrassed for her + pukey. Back to Bat For Lashes who also rules because she did Kings of Leon’s song better than them!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Y10cEM353k]

6. Vampire Weekend: I actually don’t really give this band a pass because their music is basically colonialism in MP3 form. But Rostam Batmanglij is Iranian and gay, and I always give it up for the gay ethnics (hey parents, they exist!). OH, but Vampire Weekend is all happy sounding and shit, and how can I not be into that? All the more reason to be suspicious. Shout out Miriam and Amadou!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YiUD7xOFbJw]

7. Jai Paul: Drake’s lifting of Jai Paul’s one and only song, “BTSTU,” means it is obviously the hottest shit out. Know how I know I’ve got a trace of “Hindustan Zindabad” in me? Because hearing Jai Paul’s whispery-sweet vocals used to fuel sub-par rapping (“too fucking busy/too busy fucking”) put me in a faux-murderous rage for at least five hours. Oh, shiiit!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UUBAFPIHETA]

8. Norah Jones: ROYALTY. Aside from owning a few 70s pop LPs, my parents basically don’t pay attention to any Western music. Here’s what my mom listens to now: bhajans, Bollywood oldies, Norah, bhajans. ALSO, OMG:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgZwV6ZwZU8]

9. The Kominas: In grade six, I had the biggest crush on Tony Kanal from No Doubt because he was the first cool Indian musician I had ever seen. MY ultimate 90s couple broke up before I even knew they existed: Tony + Gwen = 4eva. The Kominas have multiple (!!) brown guitar players for maximum crush potential, plus they covered a Bolly classic at BBC’s Maida Vale studios, PLUS PLUS they are like, actually, part of a movement.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DwD7qInOWtc]

10. Vijay Iyer: A former mathematician turned jazz pianist who covered M.I.A.’s “Galang” on his Grammy-nominated album, Trio? Bestill my “Marry Up” heart. [youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pOBhrnOzwXw]

The Wellness Issue