Carolann Wright-Parks: Full Interview

/In the full interview below, you’ll find Carolann Wright-Park’s reflections on running in her early thirties, her thoughts on Rob Ford, and shifting the stereotypes around poor people.

On how she got into the mayoral race

I was a rough around the edges community organizer. Because of my work I was well aware what all the issues were, and they were really important to me at the time.

It was an anti-poverty agenda, understanding that there is always that subtext of race that comes into that issue and how it plays out in terms of politics. I was not expecting to run. I'm an organizer, not usually a frontperson. It was purely the community who said, 'Look, we'd appreciate if you did this because it would highlight the issues that we work so hard from day to day. It would give a face to the issues of anti-poverty.' I covered a couple of bases in being a black woman and having come from a low-income background: I had been on assistance, got to school, and got a job to work my way out of it.

I had no political experience at that time (but now I understand that that doesn't matter!) and was not politically sophisticated at all, but I knew what the agenda was. I thought I would do this for the greater good, but I was nervous as hell and scared the day of the press conference. People thought, “This is a brave woman.” Not at all! I was terrified. But I am also a community organizer and I believe you do what you need to do to get a community agenda out there on the table.

On how race played a role in the campaign

The main organizers were anti-poverty organizers, but as I emerged as the face of the campaign, the black community became aware of this and got involved. The intention was to make sure there was cross-pollination—the intersection of these issues of race and class—making sure the worldviews of everybody who shared in Toronto were recognized and those voices could be heard through me in some way.

During that period there was a lot of police violence against young black men. The issue of race in Toronto was extremely volatile, particularly about policing. And, if you were a poor single mother in the system, and God forbid you were black, people thought it was okay to treat you a particular way. We had to not only address this in the campaign in a practical way, but get it on the Mayor's agenda.

As a black woman, I have a lens through which I see things, and race was really quite interesting. It wasn't really something that I was consciously talking about but I talk about anyway, you know? It annoys me when other people try to talk through my experience when they know they're not going through it. I was really clear with people: I'm gonna talk through my lens as a black woman who has experienced poverty, not someone who was talking about people's experiences, but talking about my own as an example of what was happening in the issues of poverty and race.

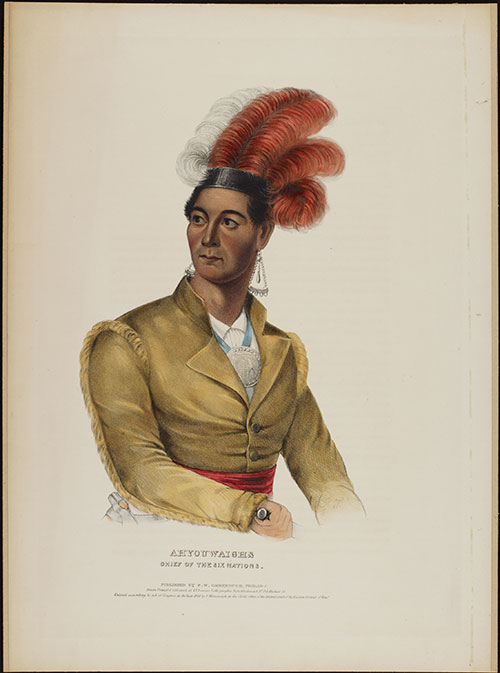

On being the first black woman to run for mayor

When I first announced, there was a pause because I don't think a black woman had ever ran before. A black man had been in city council in the 1800's at some point a long time ago [William Peyton Hubbard, a City of Toronto Alderman from 1894 to 1914] but I think I was the first black woman who had ever run, period. So, there was some pause, like 'is it serious?'

I began getting calls from the black community: 'Are you seriously going to do this and put yourself out there?' I think my community became nervous about it. As the campaign rolled out I think people became more comfortable. Speaking to the issue of race-relations is how you articulate and talk about race but at the same time be able to talk about those other issues. Those intersections are important and for me it was easy because I had experienced it all. I liked that campaign because it was really a people's campaign.

If you're a black person, people make the mistake of saying, “I'm not here to represent black people. I represent everybody.” But you are representing your community. I was representing a segment of my community. That's the reality of it. I never apologized for that.

On how crucial the issues of homelessness and low-income communities were

It was important to move those stereotypes around people who were poor. We could be smart. We could be articulate. The issue of homelessness was high on the radar at that particular moment of time. One of the overarching things was to get the city to pay attention to what was going on in Regent Park and other low-income communities: to campaign there, to pay attention, to listen to people's voices.

At the time, Toronto was not looking seriously at the issue of homelessness: we had people dying on the streets. At my time there was the G7 summit [the 14th, held between June 19 and 21, 1988] and they swept homeless people off the street for a couple of nights, and I think that was the turning point.

You can do this to impress people coming to Toronto to make it look like we don't have homelessness but that was an insult to the people who were enduring the day-to-day suffering. Being true and purposeful about the issue of homelessness is what the anti-poverty groups were trying to bring attention to: this is not a two-day thing, this is people's lives at risk here.

On increasing the vote

Young people growing up in Regent Park and St. Lawrence and surrounding areas in the city did not vote. They did not care and were not interested because they felt they were not cared about either. We wanted to change that optic and do some education around voting: You really need to begin to understand your civic duty and your voice.

I think people were at that particular time fed up with the dismissiveness around low-income communities and homelessness: things that were just not on the Mayor's agenda at that time. We wanted to let people know their voice counted. It counted on election night.

The voter turnout was excellent during that campaign because we spent time in communities doing things that were not traditionally done in civic campaigns. When people saw that it did have an impact, it really changed the leery in terms of how they saw the campaign. That kind of work needed to keep up in order for it to hold.

On what she would have done had she won

I never really thought about it at that time to be perfectly honest with you. We were so focused on the campaign issues. Education around homelessness and housing on the agenda. On increasing the vote. And contrary to opinion at that time, I knew what it was. I remember somebody from my own community saying, ‘Don't believe the hype,' and I was like, 'I am well aware of where I am and what this is and what this was about.' I was always really clear about that. Eggleton had a really strong financial team around him to make sure he got in. Had winning been what I had prepared for, I'd probably have a better answer.

On running for mayor in her early thirties, and then again for the NDP in 1990

At that particular time I did not know a whole lot about myself. You know my sons are now around the same age as me then and I think, "Oh my God," if they were to do that now. That was something I didn't think about, but I think about it now at 56. No wonder I was terrified. I barely knew myself.

The next time that I ran was in 1990 for the NDP. That was a little more intentional around winning. People thought with the traction around the '88 campaign and some of that mobilization that I'd make a good candidate. Now again being honest that wasn't my interest really in terms of career politics but I thought here's another opportunity to do some of that.

That one was closer, scarily close. That literally scared the shit out of me. I lost out by 49 votes. They were ready to do another recount and I was like, “I'm good.” It scared the incumbent enough to make him understand that the constituency was not fooling around. They wanted him and the government at that time to represent better. That Liberal government got put out that election and the NDP came in.

On if her run helped other female candidates

I couldn't really answer that truthfully because I don't know. I know people felt more comfortable running because they had said that to me, after seeing how it all worked out. There were a lot of people involved in my campaign who were councillors, female councillors, who had been very supportive so I knew it helped them frame their opportunities. I hope it did.

On why so few candidates come from marginalized communities

In politics you realize how candidates get beaten up even in the running. The States are notorious for it, and we're not much better. Your business is all out there, and it is what it is. But a lot of people do not like that kind of limelight and it becomes difficult because it's never about the issues that individual raises it's always about that individual.

For marginalized communities, when all your business is out there, it's very hard to concentrate on what you're trying to do when people are questioning your lifestyle. Like with black candidates: “They're only gonna represent black people.” I got that a lot. That we're always corrupt and the racism around that. When volunteers were canvassing for me, people would go, "Oh, I'm not voting for her. She's only going to represent black people." My sisters, who went canvassing, heard that and were completely shocked. You get marginalized about who you're going to represent.

I'd say, "Of course I am, but that's not going to stop me from representing you. This is why I'm running. I'm supposed to bring another dimension to the position of office in terms of understanding who I represent—it's a value-add.” That's how you need to answer that question.

On Rob Ford’s worldviews

Of all the things Rob Ford ever did, for which I don't think he ever should have been in office for, he had the worst worldview of anybody I had ever seen. And he said it: he's not even trying to disguise this. He said things in council about Chinese people and I was like, are you kidding me? And people didn't have a problem with it.

I was confounded [by his continual support] because if that had been any other community of people he'd have been gone before God got the news. That's a saying that we have. To make those kinds of comments, it’s about the worldview in terms of a white male with money and what that means to individuals. What that means to the people of Toronto. Those worldviews need to be challenged. But the excuses people made for it: wow, how far have we not come?

On diversity and multiculturalism initiatives

I won't join diversity committees: I just don't think they're effective because there's a lot of rhetoric around this stuff and it never gets implemented into workplaces so you see workplaces with no people of colour even to this day in Nova Scotia. Or maybe one or two—and our populations are not that small.

I'm doing training around worldviews rather than multiculturalism or, even, diversity, because you never got at self-examination and how collectively that impacted other people's worldviews. The way that we had been approaching it, people become really defensive and it shuts down the whole conversation. People want to protect what they have, and it becomes me-versus-you, us-versus-them type of scenario. I can paint a picture for you all day in terms of how racism affects my life but I want it to change so how do I create that opportunity for you to do that self-examination and to realize the impact of that? It flips the conversation a bit.

How you begin is not trying to change their worldview, but to ask the proper questions so that people begin to examine it for themselves, and to challenge themselves around how they see the world and why particular worldviews hold other people hostage. When you tell me that you don't see colour that is not a sophisticated or accurate analysis of the situation because you are seeing colour. You decided by saying that it doesn't matter—you decided that, but it does matter. How did you derive that? What do you believe? Questioning beliefs and values: how did you arrive here so that you believe this is true?

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.