Farewell to Flemingdon Park

/A co-worker once said my neighbourhood was a place he could “get weed and a hooker in less than 10 minutes.” To me it was home.

Read MoreA co-worker once said my neighbourhood was a place he could “get weed and a hooker in less than 10 minutes.” To me it was home.

Read MoreThese are our favourite Hakka Chinese restaurants in the GTA. (Why are we even telling you this?!)

Read MorePaul “Kaze” Thurton has stayed suburban on purpose.

Read MoreThis trip, twice a day, five days a week, wears the nerves raw.

Read MoreDoes being in a certain neighbourhood render a store “ethnic retail”?

Read MoreToronto's new Aga Khan museum evades the staleness that often greets “purposeful” multiculturalism.

Read MoreLike the Victorians of yore, the suburbanites enjoying Toronto's green spaces show the proper mix of exuberance and respect.

Read MoreOn the death of Jermaine Carby, who was shot by the Peel police.

Read MoreThe intersection of Hurontario and Dundas Streets is a study in supply and demand.

Read MoreThe 401 remains my urban lifeline: every exit tells a story.

Read MoreBootlegged goods, Badtz Maru and bubble tea.

Read MoreScarborough studios, Mississauga clubs and the Thornhill scene: GTA musicians on cultivating their art in and out of the downtown core.

Read MoreGrowing up as a Sikh in Alberta in the 80’s and 90’s was… interesting. It seemed like we were always in the news, whether because of kirpans in schools or turbans in the RCMP, always because we were vying for our rights to honour both our faith and our country.

Read MoreIt's evident within the opening moments of director Ursula Liang's engrossing documentary, 9-Man, that the world it explores is knotted with issues of race and masculinity. "This was something uniquely ours," says a coach, reflecting on how pioneering Asian players didn't have to worry about their larger white or Black friends "muscling in."

Read More

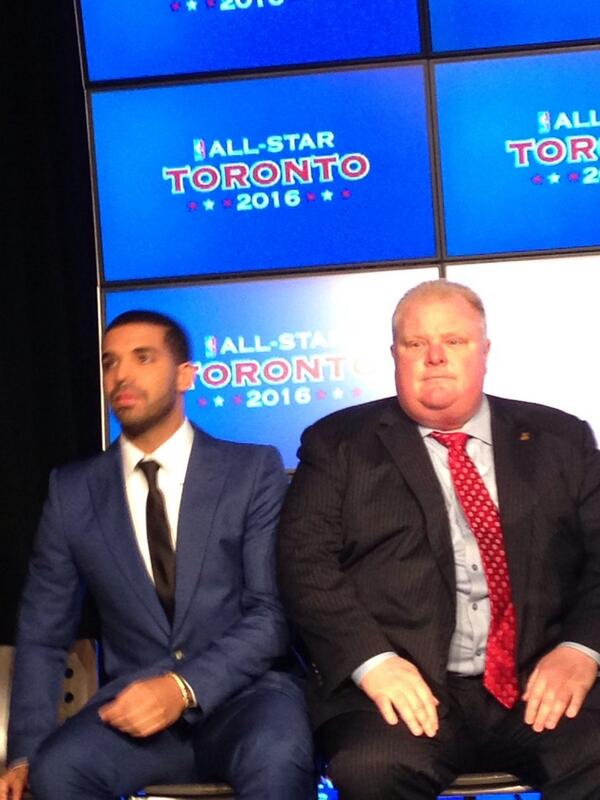

Courtesy Rob Ford's Twitter.

By Anupa Mistry

From the outside, Toronto seems like a utopia: the world’s greatest rapper calls this city home (that’s Drake, if you haven't been paying attention), gay couples are free to get married, our healthcare system is beleaguered but subsidized, and our film festival is a barometer for Oscars. Torontonians are a happy clash of cultures; almost half the population are native speakers of another language. Vogue recently named our bustling Queen West the second hippest neighbourhood in the world. THE WORLD, YOU GUYS. VOGUE.

But in the tense run-up to the municipal election later this month, there’s been a lot of drama that exposes the conservative, xenophobic face of this city’s power elites. Two female candidates, both women of colour, have publicly come forward about incidents of basic bullying hate rhetoric directed at them online and IRL, some originating from self-professed members of the ill-defined, amorphous mob known as Ford Nation.

Ah yes, so Toronto also has this mayor, whom you’ve probably heard of— and definitely laughed at. Observers of all stripes, from newspaper columnists to sidewalk Sallys, attributed RoFo’s electoral success to a platform built on outer borough discontent on the narrative of a bougie, fast-gentrifying, pedestrian and cycle-friendly downtown core that stood in direct opposition to humble, hard-working, average people. Rob’s very suss M.O. was to paint the city’s core—Manhattanizing fast, in part because of pro-business types like himself—as a wealthy, artsy-fartsy enclave guzzling a disproportionate share of the City’s fiscal resources. It also skirted over his record of boorish racism and outright homophobia.

To Ford, courting poor and/or brown constituents meant offering fast fixes while consistently, singularly voting against social policies that could directly benefit those communities across the city. His drug scandal has disproportionately impacted the communities and families connected to his dealer transactions. He refuses to acknowledge Pride. When Rob’s team announced that his cancer diagnosis was the end to his appalling stewardship of this city, a lot of people breathed a sigh of relief; surely this would be the end of Ford for Toronto. But in stepped big brother Doug Ford, with his steely death stare and watchful bull terrier stance, to announce he’d be leveraging political sympathy and antipathy toward the Ford family to run in baby bro’s stead. The deplorable, beyond surreal saga of the tenure of Mayor Rob Ford just got even more unbelievable, and that means that coming municipal election on October 27th is as locally anticipated—and as crucial, on a macro-level—as Obama ’08.

But the impact of this election should be felt beyond just who gets voted mayor and who gets voted into ward councilor positions (analysis has shown that the incumbency rate is high, at 90%), because over the past two weeks things have gotten really ugly. Kristyn Wong-Tam, a queer Chinese-Canadian councillor for the bustling Toronto Centre-Rosedale ward, and something of a media sweetheart, recently received an anonymous letter (sent from a ‘Ford Nation supporter’) filled with a bunch of racist, sexist and homophobic crap. I don’t need to repeat what was said because it pretty much amounts to geospecific YouTube trolling—it’s the same unsophisticated, fear-filled wailing that dominates Internet comment sections.

Around the same time, mayoral candidate Olivia Chow, also Chinese-Canadian, began to experience and public acknowledge a rise in racist and sexist bullying, both online and IRL. A recent investigation by the Toronto Star found Chow’s team had removed almost 1,800 “racist, sexist and other offensive posts” since announcing her campaign in March. Just last week at a community debate, open mic time was sabotaged in order to publicly fling xenophobic garbage at Chow.

Chow and Wong-Tam aren’t the only women of colour currently campaigning for political office— young women like Munira Abukar, Idil Burale and Suzanne Naraine are also angling for councilor status—but they’re a significant minority amidst all of the dudely vibes of local governance. And Chow represents the first serious mayoral bid by a non-white candidate (period) since Carolann Wright-Parks ran in 1988.

Candidates of colour are consistently questioned on their capacity to lead or portrayed as pandering to their ethnic communities, when the reality is that everyone does it—even our Prime Minister. Add being a woman to that and you’ve erected a candidate specific hurdle that the straight white men running for office are able to gleefully glide past (because they make all the rules, duh).

The sexist, anti-ethnic, anti-diversity diversion that is plaguing Toronto’s recent municipal election isn’t just an overt warning sign that things are really fucking amiss at a very high level – it’s also a missed opportunity for political opponents to be leaders and rally around Wong-Tam and Chow and take an actual stand against the ideas that make this city great. No one is saying we have to vote in Chow or Wong-Tam or Burale or even Andray Domise, the phenomenal, Diddy-loving opponent facing off against the Ford family for Ward 2 councilor, but taking lateral strides to dissuade this kind of public harassment and discrimination wouldn’t just be setting a great example— it’d be upholding the Canadian Charter of Rights.

It’s important to note that this isn’t the first time a municipal election in Toronto was marred by hate: in 2010, mayoral candidate George Smitherman was the recipient of a ton of homophobic propaganda. The Ford bros. project of confusing hard-right stupidity for populism has stoked a fire in the rapidly diluting fabric of Old (Straight, White) Toronto, but directly attributing these ideas to some freak fringe of the city serves to distract from the fact that it’s this freak fringe that is in power. Despite the fact Toronto’s entire PR angle is that it’s this diverse utopia, mainstream institutions are pitifully indicative of that breadth. I mean, there’s a reason Drake had to go stateside to make it.

This piece was published in conjunction with The Hairpin, a place on the internet to read smart things, often by women.

Race. Since Rob Ford landed in the mayoral seat, race and racism has come up a lot. Whether it’s the resurrection of dated racial slurs, claims that Rob is the Mother Teresa for young Black males, the use of well-worn stereotypes or that drunken Patois rant, Torontonians have been made to take a cold hard look at the city’s motto “Diversity Our Strength.”

And then Olivia Chow entered the race.

The non-male, non-white Chow shifted the racial dynamics and broadened the diversity of the mayoral race in one fell swoop. Before, we had a group of white candidates pandering to the ‘ethnic vote’ but with Chow in the race things changed. Or did they?

Tonight, Septembre Anderson will moderate a Twitter chat based on the issues and ideas stirred up in our Election Issue.

This edition of the Ethnic Aisle #EthniChat aims to discuss race, racism and the upcoming mayoral election and to kick start the discussion we ask, “what is the ‘ethnic vote’?”

Q1. What is the "ethnic vote," anyway?

Q2: Can you pander to the "ethnic vote" if you are not white?

Q3: Is it okay for racialized individuals to vote for Olivia Chow largely based on her not-male, not-whiteness?

Q4: Has Chow’s race helped or hindered her campaign?

Q5: Do you believe the Fords have made racial intolerance in Toronto worse or just brought it to the surface?

Find it on Twitter at the @ethnicaisle, using the hashtag #ethnichat (just one 'c'!)

In the full interview below, you’ll find Carolann Wright-Park’s reflections on running in her early thirties, her thoughts on Rob Ford, and shifting the stereotypes around poor people.

On how she got into the mayoral race

I was a rough around the edges community organizer. Because of my work I was well aware what all the issues were, and they were really important to me at the time.

It was an anti-poverty agenda, understanding that there is always that subtext of race that comes into that issue and how it plays out in terms of politics. I was not expecting to run. I'm an organizer, not usually a frontperson. It was purely the community who said, 'Look, we'd appreciate if you did this because it would highlight the issues that we work so hard from day to day. It would give a face to the issues of anti-poverty.' I covered a couple of bases in being a black woman and having come from a low-income background: I had been on assistance, got to school, and got a job to work my way out of it.

I had no political experience at that time (but now I understand that that doesn't matter!) and was not politically sophisticated at all, but I knew what the agenda was. I thought I would do this for the greater good, but I was nervous as hell and scared the day of the press conference. People thought, “This is a brave woman.” Not at all! I was terrified. But I am also a community organizer and I believe you do what you need to do to get a community agenda out there on the table.

On how race played a role in the campaign

The main organizers were anti-poverty organizers, but as I emerged as the face of the campaign, the black community became aware of this and got involved. The intention was to make sure there was cross-pollination—the intersection of these issues of race and class—making sure the worldviews of everybody who shared in Toronto were recognized and those voices could be heard through me in some way.

During that period there was a lot of police violence against young black men. The issue of race in Toronto was extremely volatile, particularly about policing. And, if you were a poor single mother in the system, and God forbid you were black, people thought it was okay to treat you a particular way. We had to not only address this in the campaign in a practical way, but get it on the Mayor's agenda.

As a black woman, I have a lens through which I see things, and race was really quite interesting. It wasn't really something that I was consciously talking about but I talk about anyway, you know? It annoys me when other people try to talk through my experience when they know they're not going through it. I was really clear with people: I'm gonna talk through my lens as a black woman who has experienced poverty, not someone who was talking about people's experiences, but talking about my own as an example of what was happening in the issues of poverty and race.

On being the first black woman to run for mayor

When I first announced, there was a pause because I don't think a black woman had ever ran before. A black man had been in city council in the 1800's at some point a long time ago [William Peyton Hubbard, a City of Toronto Alderman from 1894 to 1914] but I think I was the first black woman who had ever run, period. So, there was some pause, like 'is it serious?'

I began getting calls from the black community: 'Are you seriously going to do this and put yourself out there?' I think my community became nervous about it. As the campaign rolled out I think people became more comfortable. Speaking to the issue of race-relations is how you articulate and talk about race but at the same time be able to talk about those other issues. Those intersections are important and for me it was easy because I had experienced it all. I liked that campaign because it was really a people's campaign.

If you're a black person, people make the mistake of saying, “I'm not here to represent black people. I represent everybody.” But you are representing your community. I was representing a segment of my community. That's the reality of it. I never apologized for that.

On how crucial the issues of homelessness and low-income communities were

It was important to move those stereotypes around people who were poor. We could be smart. We could be articulate. The issue of homelessness was high on the radar at that particular moment of time. One of the overarching things was to get the city to pay attention to what was going on in Regent Park and other low-income communities: to campaign there, to pay attention, to listen to people's voices.

At the time, Toronto was not looking seriously at the issue of homelessness: we had people dying on the streets. At my time there was the G7 summit [the 14th, held between June 19 and 21, 1988] and they swept homeless people off the street for a couple of nights, and I think that was the turning point.

You can do this to impress people coming to Toronto to make it look like we don't have homelessness but that was an insult to the people who were enduring the day-to-day suffering. Being true and purposeful about the issue of homelessness is what the anti-poverty groups were trying to bring attention to: this is not a two-day thing, this is people's lives at risk here.

On increasing the vote

Young people growing up in Regent Park and St. Lawrence and surrounding areas in the city did not vote. They did not care and were not interested because they felt they were not cared about either. We wanted to change that optic and do some education around voting: You really need to begin to understand your civic duty and your voice.

I think people were at that particular time fed up with the dismissiveness around low-income communities and homelessness: things that were just not on the Mayor's agenda at that time. We wanted to let people know their voice counted. It counted on election night.

The voter turnout was excellent during that campaign because we spent time in communities doing things that were not traditionally done in civic campaigns. When people saw that it did have an impact, it really changed the leery in terms of how they saw the campaign. That kind of work needed to keep up in order for it to hold.

On what she would have done had she won

I never really thought about it at that time to be perfectly honest with you. We were so focused on the campaign issues. Education around homelessness and housing on the agenda. On increasing the vote. And contrary to opinion at that time, I knew what it was. I remember somebody from my own community saying, ‘Don't believe the hype,' and I was like, 'I am well aware of where I am and what this is and what this was about.' I was always really clear about that. Eggleton had a really strong financial team around him to make sure he got in. Had winning been what I had prepared for, I'd probably have a better answer.

On running for mayor in her early thirties, and then again for the NDP in 1990

At that particular time I did not know a whole lot about myself. You know my sons are now around the same age as me then and I think, "Oh my God," if they were to do that now. That was something I didn't think about, but I think about it now at 56. No wonder I was terrified. I barely knew myself.

The next time that I ran was in 1990 for the NDP. That was a little more intentional around winning. People thought with the traction around the '88 campaign and some of that mobilization that I'd make a good candidate. Now again being honest that wasn't my interest really in terms of career politics but I thought here's another opportunity to do some of that.

That one was closer, scarily close. That literally scared the shit out of me. I lost out by 49 votes. They were ready to do another recount and I was like, “I'm good.” It scared the incumbent enough to make him understand that the constituency was not fooling around. They wanted him and the government at that time to represent better. That Liberal government got put out that election and the NDP came in.

On if her run helped other female candidates

I couldn't really answer that truthfully because I don't know. I know people felt more comfortable running because they had said that to me, after seeing how it all worked out. There were a lot of people involved in my campaign who were councillors, female councillors, who had been very supportive so I knew it helped them frame their opportunities. I hope it did.

On why so few candidates come from marginalized communities

In politics you realize how candidates get beaten up even in the running. The States are notorious for it, and we're not much better. Your business is all out there, and it is what it is. But a lot of people do not like that kind of limelight and it becomes difficult because it's never about the issues that individual raises it's always about that individual.

For marginalized communities, when all your business is out there, it's very hard to concentrate on what you're trying to do when people are questioning your lifestyle. Like with black candidates: “They're only gonna represent black people.” I got that a lot. That we're always corrupt and the racism around that. When volunteers were canvassing for me, people would go, "Oh, I'm not voting for her. She's only going to represent black people." My sisters, who went canvassing, heard that and were completely shocked. You get marginalized about who you're going to represent.

I'd say, "Of course I am, but that's not going to stop me from representing you. This is why I'm running. I'm supposed to bring another dimension to the position of office in terms of understanding who I represent—it's a value-add.” That's how you need to answer that question.

On Rob Ford’s worldviews

Of all the things Rob Ford ever did, for which I don't think he ever should have been in office for, he had the worst worldview of anybody I had ever seen. And he said it: he's not even trying to disguise this. He said things in council about Chinese people and I was like, are you kidding me? And people didn't have a problem with it.

I was confounded [by his continual support] because if that had been any other community of people he'd have been gone before God got the news. That's a saying that we have. To make those kinds of comments, it’s about the worldview in terms of a white male with money and what that means to individuals. What that means to the people of Toronto. Those worldviews need to be challenged. But the excuses people made for it: wow, how far have we not come?

On diversity and multiculturalism initiatives

I won't join diversity committees: I just don't think they're effective because there's a lot of rhetoric around this stuff and it never gets implemented into workplaces so you see workplaces with no people of colour even to this day in Nova Scotia. Or maybe one or two—and our populations are not that small.

I'm doing training around worldviews rather than multiculturalism or, even, diversity, because you never got at self-examination and how collectively that impacted other people's worldviews. The way that we had been approaching it, people become really defensive and it shuts down the whole conversation. People want to protect what they have, and it becomes me-versus-you, us-versus-them type of scenario. I can paint a picture for you all day in terms of how racism affects my life but I want it to change so how do I create that opportunity for you to do that self-examination and to realize the impact of that? It flips the conversation a bit.

How you begin is not trying to change their worldview, but to ask the proper questions so that people begin to examine it for themselves, and to challenge themselves around how they see the world and why particular worldviews hold other people hostage. When you tell me that you don't see colour that is not a sophisticated or accurate analysis of the situation because you are seeing colour. You decided by saying that it doesn't matter—you decided that, but it does matter. How did you derive that? What do you believe? Questioning beliefs and values: how did you arrive here so that you believe this is true?

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

By Desmond Cole

For the past six years, I’ve been hosting a public conversation about citizenship and inclusion as project coordinator of City Vote, an effort to extend municipal voting rights to all permanent residents of Canada. Support for the initiative, while on the rise, is still lukewarm at best. A 2013 poll determined that just over half of Toronto residents are opposed to the idea – an improvement from my early days on the campaign, but still surprising in a city where half of the inhabitants were born abroad. Last year Toronto city council endorsed a motion on permanent resident voting by 21-20, the narrowest of margins (the city has asked the province, who has the final say on the issue, to consider it).

City Vote supporters often ask me why people oppose giving non-citizens the local vote. While I don’t have a complete answer, I’m convinced that the presumed supremacy of our country’s British parliamentary democracy is an important factor. The British colonized this land and imposed their system of government, not only on all those who would come after them, but on the people who were already here. The treatment of Canada’s indigenous people as outsiders, as aspirants to British civilization, can teach us a lot about the struggle to enfranchise today’s non-citizen immigrants.

When people object to City Vote’s mission, they cite reasons they feel are practical and almost unquestionable: that non-citizens do not understand Canadian history, society and culture; that they have not demonstrated the proper loyalty; that giving non-citizens a vote would devalue the votes of citizens; that non-citizens value other things above voting, and therefore have no use for it.

All of these arguments were made about indigenous people as Canada established and amended its voting regimes. All of them rely on the apparent superiority of our current form of government, and by extension, the superiority of the white British elites who established it and used their power to categorize and regulate all non-whites.

When Canada held its first federal election in 1867, the country’s diverse indigenous inhabitants were not included; with few exceptions, the same was true for the provincial and municipal elections that preceded and followed Confederation. At first, most jurisdictions saw no need to make rules for prohibiting indigenous voters, who were assumed to be government property. But in 1865, British Columbia explicitly banned “Indians and Chinese” from voting in its elections. Even before Canada became a country, “Indians,” whose land the British had taken as their own, were excluded alongside “Chinese,” who had migrated to work or trade.

In 1885, Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, argued that Chinese people were not fit to vote because they possessed "no British instincts or British feelings or aspirations.”

“The Chinese are not like the Indians, sons of the soil. They come from a foreign country; they have no intent, as a people of making a domicile of any portion of Canada…. They are, besides, natives of a country where representative institutions are unknown, and I think we cannot safely give them the elective franchise.”

Macdonald’s fear that people raised under foreign governments couldn’t be trusted is, sadly, still with us. Likewise, for the indigenous “sons of the soil,” Macdonald and Parliament had created the Indian Act, to regulated their day-to-day existence. Parliament had also provided in 1868 for “voluntary enfranchisement”, a system which gave indigenous people the right to vote if they agreed to renounce their status as Indians. Professor Larry Gilbert has written that enfranchisement was “based on the theory that aboriginal peoples in their natural state were uncivilized. Once an aboriginal person acquired the skills, the knowledge and the behavior valued by civilized society, the aboriginal person might qualify for citizenship."

The arbitrary classification of today’s immigrants, who are encouraged to graduate into civilized Canadian citizens before being granted the privilege of voting, is nothing new. Rules about voting have been applied differently to different groups of people, and race has always been a defining factor.

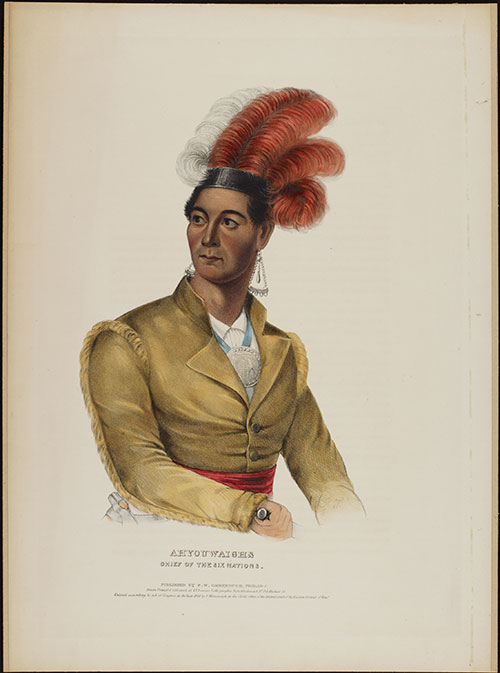

Ahyouwaighs, or John Brant. Painting by Charles Bird King.

Take the example of John Brant, an indigenous man who was elected to the Upper Canada Assembly, but whose election was subsequently nullified. As professor Veronica Strong-Boag wrote in 2002, “lease-holding, the proprietorship said to exist on Native reserves, was held not to count as property for the purpose of suffrage. Thus many of Brant's supporters were disenfranchised."

While indigenous people’s property rights were said not to count, the rights of white British subjects were upheld, and were sometimes even accepted in spite of the rules. As recently as 1969, British subjects who had lived in Canada for a year were eligible to vote, even South African citizens, although the country left the Commonwealth in 1961. Not by coincidence, South Africa has long contained Africa’s largest percentage of white inhabitants.

Today, there are no voting exemptions for property holders who are not Canadian citizens. As Ryerson professor Myer Siemiatycki has pointed out, Toronto’s municipal voter’s list includes property owners who are not residents of Toronto, but are still extended the right to vote, if they are citizens. Meanwhile, Siemiatycki notes, non-citizen property holders who do live here (and pay taxes here, and send their kids to school here, and otherwise contribute to and use the city) are excluded from voting at any level of government.

Before 1971, almost 80 per cent of immigrants to Canada were European – in other words, white. Between 2006 and 2011 more than 80 per cent of immigrants came from Asia, African, the Caribbean, and Central and South America.

As the makeup of our country has changed, so have restrictions for voting rights. For more than a century, proof of property rights, residency and taxation were good enough to allow British subjects to vote at the local level. Today, citizenship is the new standard for today’s mostly racialized immigrants. Yet non-citizen British subjects could vote in municipal elections until 1985 in Ontario; they retained the municipal vote in Nova Scotia until 2007.

We must also remember that other classes of non-citizen residents – temporary foreign workers, refugees, student visa holders, and people without any documentation – are not part of the current conversation to extend voting rights. Indeed, the mere mention of these groups, particularly undocumented people, is a non-starter for politicians.

So it was with indigenous people in the early days of Confederation, when politicians like Conservative George Foster had to assure his colleagues that enfranchisement was not meant for all indigenous people: “it is not the intention nor is it in the power of this Bill to enfranchise the wild hordes of savage Indians all over the Dominion.”

The fact that we can even have a conversation about non-citizen voting proves that we have made great strides towards a more inclusive country. But the continued resistance to change is based on an outdated and ultimately racist view that outsiders, particularly racialized ones, must prove their allegiance to a British system founded on assumptions of white supremacy.

During the 1885 debates on electoral reform, Liberal MP Peter Mitchell stated, “I would give to everyone who has assumed the same position as the white man, who places himself in a position to contribute towards the general revenues of the country, towards maintaining the institutions of the country the right to vote.” Although few today would be so blunt, the same attitude applies.

Adwoa Afful

@thestreetidle

Desmond Cole

@desmondcole

Supriya Dwivedi

@supriyadwivedi

Kelli Korducki

@kelkord

John Michael McGrath

@jm_mcgrath

Jaime Woo

@jaimewoo

Chantal Braganza

@chantalbraganza

Joan Chang

@joanchang

Helen Mo

@helenissimo

Neha Thanki

@nehathanki

Septembre Anderson

@septembreA

Simon Yau

@simyau

Navneet Alang

@navalang

Denise Balkissoon

@balkissoon

Renee Sylvestre-Williams

@reneeswilliams

By Kelli Korducki

“I'm not male. Not white. Want to start there?”

This was how, in an April Twitter chat, Olivia Chow fielded a question from Toronto Star reporter Daniel Dale on how she might politically distinguish herself from the Miller years. A non-answer on the policy level, Chow's response touched on questions that had been bubbling since well before she announced her candidacy.

From the moment city chatter settled into election mode—roughly sometime between Crackgate and early 2014—there was speculation over whether Chow could rally the Chinese communities in Scarborough and North York to tip the vote in her favour. As Ethnic Aisle contributor Simon Yau pointed out in Toronto Life, Ford's fiscal conservativism can be an appealing sell for practical-minded Chinese immigrants like his parents, who prioritize hard work and self-sufficiency over expanding municipal services through tax hikes. But Yau explained his parents weren't necessarily opposed to voting for Chow: “She's Chinese,” he noted, “and that may be enough.” Maybe something as simple as ethnic solidarity would bring a definitive end to any hope of Ford More Years.

And so we have Chow: the only not-male, not-white frontrunner for the mayoralty. As of the most recent polls, it looks increasingly likely that she'll be bested in this race by the very male, and quintessentially white John Tory.

The scare-quoted “ethnic vote” is something we've touched on here at the Ethnic Aisle, in the context of white candidates clumsily trumpeting inclusivity in exchange for ballots. But the meaning of the term changes when the candidate in question is herself an ethnic minority, for whom being “down” with ethnic communities is perhaps more than an obligatory performance.

While Chow hasn't explicitly positioned herself as a minority candidate (how that would even take shape is anybody's guess), her first major campaign fundraiser was held at a dim sum banquet in Scarborough, where Chinese community leaders sung her praises to a receptive crowd using both Cantonese and Mandarin. Chow also adopted Toronto's newly introduced 437 area code in order to secure a triple-eight number sequence in her campaign's official phone number; in Chinese culture, the number eight, and triple eights especially, are seen as arbiters of good fortune.

And yet there has been little talk of Chow potentially becoming Toronto's first non-white mayor, or what that would signify for the ethnically diverse city she would represent. In the meantime, the “anyone but Ford” cabal is evacuating her camp faster than if a hurricane personally knocked on every one of their front doors. Maybe she's too progressive or not progressive enough; maybe it's a question of charisma. Or, maybe—and here we can all share a communal wince—it's “not-white, not-male” that's the sticking point. Slurs have been hurled (“Go back to China!” at a recent debate by a Ford-supporting heckler); her accented English hasn’t gone undiscussed. Still, there's no real way of knowing whether Chow's ethnicity has helped or hindered her mayoral campaign. We can only presume that it's done both, and almost certainly one more than the other, but we're left to gut feelings and educated guesses to determine which—and, well, neither one of these research methods is exactly scientific.

What we do know is that the past four years—the past Ford years—have been a boon to bigotry. We're well beyond the point of pretending the mayor has any possibility of redeeming himself from his demonstrated misogyny, his racism, his homophobia. These behaviours have left a starker stain on the Ford mayoralty than his obstinacy or self-destructive appetites.

Worse than the unflattering light they've cast on our entire city, the past four years have been shot through with the kind of hatefulness that's viscerally painful to confront head-on. Whether or not we were complicit in Ford's election, we were all unwittingly signed up for his reality show in 2010. It's easier to avert the collective gaze than to dwell on the magnitude of Ford's ignorance, and the stranger-than-fiction plot points of his reign have done a good job of distracting from its ugliness.

Chow is the anti-Ford, and not only because she occupies a space on the opposite end of the political spectrum. The reality is much grimmer: as a woman of colour, she is the embodiment of all that our mayor disregards. Her sheer personhood defies the politician a majority of voters selected to represent our city four years ago. That's a tough pill to chew, and an even tougher one to swallow.

The Wellness Issue